- Home

- Laura Jarratt

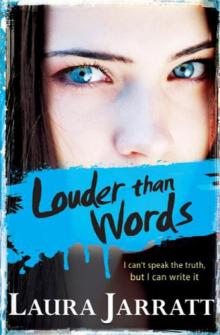

Louder Than Words Page 10

Louder Than Words Read online

Page 10

CHAPTER 21

I nearly didn’t write about what happened to me next as, after all, this has always been about Silas and not me, but then I found I couldn’t leave out my part, or Josie’s, and have it still make sense. Our stories are so intertwined, like the three strands of a braid, that I have to tell it all.

It was, predictably, Silas that I gave the note to as soon as we got home from school. He glanced at it and then sat down on the couch. ‘Why now? I’m pleased, of course. I think it’s the right thing to do, have done for ages, but why now?’

I took the note back and scribbled on it. Josie talked me into it.

He sighed. ‘I’m glad someone did. So you want me to tell Mum for you?’

More scribble. She might listen to you.

He made a huffing noise and raised his eyes to the ceiling. ‘You think so? Never mind, I’ll give it a go?’

When? my eyes asked.

‘Tonight,’ he said. ‘As far as I know she’s home tonight. I’ll cook and then I’ll drag her to the table. We’ll talk about it then.’

My brother set the stage well. He laid the table and even chilled a bottle of white wine for our mother. She’d probably let him have a glass. He wasn’t a big fan, but he’d sip it to be polite. ‘Makes her think of me as more of an adult,’ he said as he put a bowl of tossed salad on the table, ‘which is not a bad thing for the purposes of this conversation.’ He’d thrown together a bag of frozen seafood with some pasta sauce and cooked spaghetti. It would taste great, I could tell, from the smell wafting through the house. He made dessert too. ‘Keep her at the table longer,’ he said with a wink. ‘Wear her down!’ It was only a mango sorbet and ice-cream layer mix in some glasses, but it looked good.

Mum appeared at half six, just when we’d begun to think she wasn’t coming back after all. Silas cleared his glower and bit his tongue until he could manage to say, ‘Busy day?’ with reasonable aplomb.

She showed us startled eyes, as if she hadn’t fully realised we were there. Ghost children, that’s what we were.

I’d always known that of myself, even from the earliest days before Dad left. I might as well have been a wraith around the house for she never saw me except to notice some misdemeanour. And as I tried so hard to stay out of trouble, in practice she seldom did see me.

‘Not bad. I had a meeting with a broker who wants some pieces for an overseas client. It’s a reasonably large commission but drearily dull, alas.’

‘I cooked,’ said Silas. ‘It’s ready if you want to sit down. So what does the drearily dull client want you to do?’

I laughed secretly at my brother getting what he really wanted in a sneaky sandwich with the commission talk. Funny and clever. But that was my brother.

He ushered Mum through to the dining room before she had time to process what he was up to. I zoomed through to the kitchen and appeared at his shoulder with the wine bottle just in time. ‘Nice one,’ he whispered out of our mother’s earshot as he filled her glass.

‘He’s Icelandic, I understand. Wants me to do a series of paintings based on a theme of betrayal.’

Silas looked confused. ‘That sounds quite open-ended. I would have thought it would be interesting. You know, it’s not one of those “Give me a six-by-four canvas of a tree in winter” types.’

‘Betrayal though,’ she said with distaste, plucking a breadstick from the glass and nibbling delicately on it – I envied my mother that, the ability to nibble delicately. ‘So . . . overdone at the moment. Mark Rackham’s just exhibited with that as a theme, and then Judy Renfrew did a set of sculptures. Not to mention Clive Harding’s show only last year.’

‘So why didn’t he go to them? He must like your work, I guess.’ Silas waved at me to bring the food through from the kitchen while he kept her talking.

‘Yes, he’s a big fan apparently. And he thought nobody would convey betrayal more perfectly than me, or so his broker says.’

Silas laughed. ‘Is this some personal thing for him, this theme of betrayal? Has he got dumped recently?’

Our mother winced. ‘Silas, try to have some empathy.’

Ha! That was a joke coming from her!

‘Yes, I understand he does want me to work on this theme for very particular reasons. I believe his marriage ended a few months ago.’ She shook her head sadly. ‘It’s a painful time for him.’

Artistic people were allowed to feel pain. In fact, in my mother’s eyes, it was only artistic people who felt true pain. The rest of us Philistines didn’t have the temperament to suffer. I think she viewed us like cows – too placidly bovine to hurt much.

‘Oh,’ Silas replied, serving pasta on to the plates. ‘Bummer. I guess he really loved her very badly if he’s coughing up to pay you for a series. It’s not like you’re cheap.’

‘You cannot set a price on art,’ she answered with a pained expression.

Silas refrained from pointing out that no, actually, she set a hefty price tag on hers. Not that either of us minded. After all, her art paid for everything. It was the two-facedness of it that got on our nerves, but she would never see it like that.

She took a small bite of the pasta. My mother was one of those uber-annoying women who never got pasta sauce on her chin. Whereas I had to surreptitiously check over my face with my hand every few mouthfuls in case I was smeared with it. ‘This is good,’ she said. ‘Did you cook it from scratch?’

‘More or less,’ Silas said, ignoring that the seafood came ready mixed in a bag from Waitrose and the sauce was out of a tub.

‘Hmm, well done. You know, perhaps you have some ability as a chef. Have you considered exploring that as an avenue?’

To our mother, computing was not really an appropriate thing to be gifted in. You could tell she thought there was something terribly vulgar about it.

‘It’s something to think about,’ Silas said, ducking the issue quickly before he got a lecture on how life without art was mere existence. Our sister Kerensa’s maths genius was just allowable because everyone knew the link between maths and art and music. Look at Da Vinci: artist, sculptor, musician, mathematician.

Silas waited until her mouth was full and then added, ‘Rafi has something she wants to ask you.’

‘Rafi?’ My mother forgot herself so far as to speak with her mouth full. And she sounded rather as if she’d forgotten who I was.

Silas’s eyes flashed with annoyance and he looked away. ‘Yes, she wants to go and see someone. I looked this stuff up and there’s a choice – speech and language therapist or psychologist.’

My mother opened her mouth to give her views on that.

Silas cut in before she could get started. ‘So I asked Rafi who she’d rather see, and she said the speech and language therapist because she hated the last psychologist she had.’

My mother ate another mouthful of spaghetti thoughtfully. ‘Yes, I recall that one. Positively demonic! And no understanding of the condition either.’ She looked at me as if I was an unusual variety of beetle found under a rock. ‘Not that it’s easy to understand at all. Heavens, nobody knows that better than we do. But one expects a professional to have some idea. I think this was the first case she’d ever come across in the flesh.’ She tutted. ‘And I doubt her textbook knowledge was up to much either.’

‘So can you arrange it then? For her to see a therapist?’

She took a sip of wine. ‘I suppose so. There may be a waiting list. There always seems to be a waiting list these days for any health issue, especially mental health. Margaret – you remember Margaret, did those sculptures with driftwood and steel that became fashionable a few years ago – told me she had to wait months to see someone to talk about her depression.’

Mental health. Thanks, Mum.

I hate that term ‘mental health’. Nearly as much as I hate ‘mentally ill’. Because everything mental comes from your brain or some other hormones acting on it. And your brain’s an organ, just like your heart or your kidneys. You don’

t get people saying they are cardiacally ill and then have others make fun of it or shy away from them like it’s catching. It’s stupid! How is having something wrong with your brain different to having a broken leg or your pancreas not working properly?

‘Well, if there’s a long waiting list, can’t she go to see a therapist privately?’ Silas asked patiently.

My mother nodded. ‘I would imagine that’s possible. Though it may be a fearful waste of time and money if she behaves as she did last time and refuses to engage with them.’

‘She won’t. Because this time it’s her choice. Rafi wants to go for herself, not because she’s being made to or the school has said she has to. She wants to see if she can get better.’

The only word to describe the expression on my mother’s face was astonished. And I realised that for years now she had never seriously considered the possibility that one day I might talk again.

Nice.

‘Oh and there’s one more thing,’ Silas said.

‘What’s that?’

‘She wants me to go with her, not you.’

I set her on my pacing steed,

And nothing else saw all day long,

For sidelong would she bend, and sing

A faery’s song.

(John Keats – ‘La Belle Dame Sans Merci’)

CHAPTER 22

Dad, I finally did it!

I’ll tell you the whole thing because I want you to see how amazing she is and, well, I’ll have to tell you all of it for you to see that. Here goes: it’s a bit like telling a story, I suppose, so I’ll try to make it interesting for you.

My heart was pounding in my chest. She had said she’d be here, at the café opposite the bus station, waiting for the last bus home, but I still exploded inside like a cascade of fireworks when I saw her sitting there in the window seat.

I stopped for a moment to look at her before she saw me so I could drink in the sight of her. She’d answered my text when I’d asked if we could catch up with each other to say yes, here was where she’d be so come and find her. And I’d run there like an eager little puppy, but I didn’t care. This could be risking everything because if she blew me out now I might never see her again. Or I’d see her only when she was hanging out with Rachel, Toby or the others, which would probably be worse.

She sipped her coffee, her small fingers curled round the cup, and it was unthinkable that I could lose her.

This had to work.

Her face didn’t light up at the sight of me, but I can wait for that if only it does one day. She isn’t like the other girls, I need to remember that. I have to work to deserve her. I said hi and went to the counter to get another coffee for her and one for me.

She won’t bring the kind of loving and being loved that my friend Sam describes, which sounds like sinking into a warm bath after a cold day with exhausted, aching muscles.

No, loving Lara . . .

. . . loving . . . I still can’t quite believe I’m saying that to myself . . . me . . .

. . . loving Lara will be like standing out in a thunderstorm and, even if she never loves me back, being allowed near her is compensation enough.

Just so long as she doesn’t already love someone else.

When I had that thought, I had a burst of jealousy so strong it made me take a step back from the counter.

She didn’t, did she?

But I hardly knew anything about her. I liked that, liked the mystery. She didn’t give everything away about herself in five minutes like some girls did, babbling on and on as if they couldn’t shut up.

But Lara’s more than a closed book; she’s padlocked.

Another challenge then, to learn more about her.

I took the coffees back to the table. She made no move to start a conversation, but thanked me and swapped her finished cup with the full one. Then she watched through the window as an old woman at the bus stop berated two teenage boys for queue jumping.

‘Our society has no respect for the old. It makes us poorer,’ she said and took a sip of the fresh coffee.

I just watched her. It wasn’t that I didn’t agree. In some ways I find myself agreeing with everything she says. She makes me think about things I’d never considered before, look at the world in a new way.

Suddenly she stood up, pushed her chair back in a rush and ran out. Outside events had taken a turn for the worse. The two boys were yelling at the old woman and one of them had stepped forward menacingly. I got up and ran after Lara.

When I got out there, she was up in the faces of the two boys – or as up in their faces as someone of her height could be – standing between them and the old woman and yelling her head off. They looked startled for a moment, then their expressions turned ugly. As I arrived by her side, they’d broken out into the usual torrent of abuse dumb boys use when faced with a smart girl they feel threatened by.

This was going to get messy. The old woman had retreated further back, looking around for help. She was scared, but she wasn’t giving way either.

I opened my mouth to intervene, fully expecting I could end up getting my head kicked in, but what else was there to do? The smaller boy brought his fist up and swung at Lara’s face. I went for him.

But I didn’t react as fast as Lara. She brought her arm up to block the punch and simultaneously raised her leg to kick him in the stomach. The kid dropped to the ground screaming – it was like something from a martial arts film.

‘It’ll be your teeth next time,’ Lara yelled. ‘Weren’t expecting that, were you? Think women can’t look after themselves? Well, think again!’

We were attracting quite a lot of attention now. A group of men wearing the uniforms of the timber yard across the road came over to help.

‘I’d get out of here if I were you,’ I said to the boys. ‘You’re in way over your heads now.’

One of the men put his arm round the old woman, who he’d seen was upset even from where he’d been standing, and the others stood staring the boys out. The one on the ground hauled himself to his feet and his friend pulled him off into the road. They hobbled off together without another word.

Lara dropped her fighting stance and turned to me. ‘Do you think the coffee’s still hot?’

Back in the café, the coffee had not yet gone cold, so Lara sat down to finish it.

‘Where did you learn to do that?’ I asked her.

‘The kick-boxing? I started doing it a few years ago. I got fed up with people like them trying to throw their weight about because I’m a girl and because I’m small.’ She narrowed her eyes at me. ‘In a world that’s so violent towards women, we need to be able to protect ourselves.’

I would have protected you, I said silently to myself, but had to face facts that she’d probably done a better job than I could have. But this was a chance to dig for some information. ‘So do you still take classes?’

‘Occasionally, when I have time.’ She’d thrown up a guarded expression as soon as I asked the question.

‘What else do you do with your time? Do you go to college?’

‘What is this? The Spanish Inquisition?’

‘No, I just find you interesting, that’s all.’

She raised an eyebrow. ‘No, I don’t go to college. I work full time in Toby’s mum’s shop. I used to go, but I dropped out a few months ago. Didn’t like the course.’

‘Don’t you want to go to uni?’

‘No.’

‘So what will you do?’

‘I want to spend a few years campaigning and travelling. Right now I’m working and saving money so I can go to Africa and do some volunteer work in the villages, building wells and helping improve the water supplies.’

I thought of how I want to go to Oxford to read computer science, but what’s faffing around with code compared to getting out in the world and saving lives hands on by providing clean water? How many lives are lost each year according to that guy, Dillon, because people don’t have access to it? I can�

�t remember the exact figure, but it’s a staggering amount.

‘What do your parents think of that?’ I asked. ‘Will they be worried about you?’

She shook her head and shifted her eyes away from mine. ‘We don’t get on. They lead their lives and I lead mine. They give me an allowance and I accept it for now because it enables me to pay the rent on my flat and buy food, and that means everything I earn I can put towards travelling.’ She looked back at me again. ‘It’s important to see what you’re fighting for and really be part of that, otherwise you risk being nothing more than a sound bite.’

‘Yeah, I guess.’

It scared me a little, just how far I’d have to shift my expectations to be with this girl, but to give up now would be unimaginable. I would, I realised, do anything.

Her lip curled. ‘You guess?’

I shook my head at her. ‘I know you think it sounds lame, but sometimes you . . . you rob me of words. I don’t know what to say to you because my brain’s frantically trying to process some new stuff you’ve thrown at me and my mouth can’t keep up.’

She looked intrigued despite herself. ‘What do you mean?’

‘I mean you’re not like anyone else I know and you make me think differently about stuff and that’s great. Really great. More than great, it’s amazing. But I want to pause and think about what you say. And you throw a grenade right out at me the second I don’t give an answer exactly the way you think I should.’

‘So what you mean is “shut up, Lara, sometimes, and let me just think”, yes?’ She laughed. ‘OK, I’ll concede that point – for now.’

She must have believed I was going to be around her or she wouldn’t have said it. I whooped inside. But I had to keep it cool. She expected that and I had to deliver no matter how excited I secretly felt. ‘That would be good, yeah.’

She laughed again. ‘I can be full-on, I know that and I make no apologies for it. Without passion, life is grey and you may as well be one of the sheeple.’

Life would never be grey around her.

Louder Than Words

Louder Than Words