- Home

- Laura Jarratt

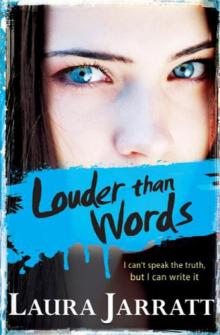

Louder Than Words Page 13

Louder Than Words Read online

Page 13

Choking. Feel faint if it gets really bad.

‘She stopped breathing once,’ Silas said. ‘It was at school when a new teacher tried to make her speak. The teacher kept shouting at her and she stopped breathing. She only started again when she passed out.’

Andrea compressed her lips. ‘That must have been very frightening for you.’

It was. I thought I was going to die. I tried to forget about that incident and Silas knew it so he must have thought it was important to bring it up. I didn’t listen to Silas explain what happened as Andrea prompted him for more information. I didn’t need to listen – I remembered it all too well.

I was ten. We’d just got a new class teacher because our old one had left to go to another school halfway through the year. I wasn’t sure what went wrong at the time, whether the teacher hadn’t been told about my condition or if she just didn’t believe in it. It turned out later that it was the latter, but we only found that out after Silas told my mum what had happened and she stormed into the school and went off like a nuclear bomb. I was mad with Silas for telling, but at least it meant I didn’t have to be in the woman’s class any more.

She’d looked annoyed when she read out the names from the register and I didn’t answer but raised my hand instead. I cringed inside at her expression. I knew she was thinking what a nuisance I was. They all secretly thought that, even my last teacher who’d been one of the nicer ones. I was more work for them than the others. She didn’t make any comment in registration though. It was later at reading time that the trouble began.

She was going round the class, telling people to read a page each from our books. I still remember the book: it was Charlotte’s Web, which I loved up until then, but I’ve never been able to touch it since. She started with the person straight in front of her and then went down each row of desks and back up again. I must have had some sense of what was brewing because I recall that as it got closer and closer to what would have been my turn, I started to get a tummy ache. It wasn’t that unusual for this to happen. I often got mild anxiety that a teacher would forget and try to make me read whenever we did this kind of thing, but this time it was bad. I held my stomach and tried to rub it without anyone noticing. Still, the moment she said, ‘Rafaela, your turn,’ it took me a second to process that my worst fear was really happening. It was so often a nightmare for me that I thought for a moment I was in a dream and tried to wake up.

Her voice came again, sharper this time. ‘Rafaela! Stop daydreaming. Your turn to read!’

I stared at her helplessly.

‘Don’t look at me in that vacant way, child!’ she snapped. ‘Pay attention. Page 83, begin at the top.’

Another girl put her hand up, looking at me nervously. She was ignored as the teacher got up and began to come over.

‘Please, Miss,’ the girl said hesitantly, ‘Rafi can’t talk.’

The teacher whirled round. ‘And who asked for your opinion, young lady?’

The girl fell silent and put her head down.

My throat was tightening painfully, a tightness that was spreading down into my chest as the woman got closer.

I remember her shoes: black patent court shoes with a scuff on one toe. I remember I focused on the scuff as I tried to breathe. One in, one out, I told myself, attempting to count so I didn’t forget how to do it. One in, one out.

She stabbed her finger at the page. ‘From here! Now read!’

One in, one out.

She bent over me. ‘I will not tolerate this nonsense. Begin reading now!’

One in . . .

But the breath wouldn’t come in. My chest was too tight.

She was angry. Her face was reddening as her frustration with me built.

I couldn’t do it, I couldn’t.

I shook my head.

And that was when she really exploded.

‘How DARE you shake your head at me?’ she shouted. ‘I don’t know who you think you are, young lady, but I do not accept behaviour like that from anyone in my class. Now, I have given you an instruction and you had better do as you are told.’

Silas said to me after that she’d probably gone so far by this point that she couldn’t have backed down even if she could see it wasn’t working or she’d lose face in front of the other kids.

‘You WILL do as you are told,’ she yelled as I still didn’t begin reading.

I couldn’t breathe in or out by this time. I heard the other kids talking about it the following week when I returned to school and apparently I went purple.

‘If you don’t do as you are told, we will all sit here until you do read. And if this whole class has to miss their break and playtime at lunch because you won’t do as you are told, then it will be very much the worse for you, madam, won’t it?’

My stomach cramped so badly that I fell forward on to the desk.

‘READ!’

I couldn’t hear her any more. The ringing in my ears got too loud. They said I fainted and fell to the floor. They said she thought I was faking it at first and carried on shouting at me to get up and stop being so silly, but then a teacher came in from another class to see what all the fuss was about. She called for the Headmistress, who had me taken to the sickroom where they kept me for the rest of the day. The school nurse stayed with me, but nobody called my mum. Silas said with disgust that they were probably hoping to cover it up. After all, I wouldn’t talk. But one of the little girls in my class, I think the one who had tried to speak up, went over to the netting that separated the prep department from the senior school and got someone to find Silas. She told him what had happened.

When I look back on that now, she could have become a friend, if I’d had the courage to realise it. It wasn’t until I made friends with Josie that I began to recognise signs of friendship, but that girl did two nice things for me that day. If I’d tried to be friends with her after that, maybe my time in the prep would have been different.

Andrea stood up. ‘I think I’ll make us a drink and get the biscuits out,’ she said. Her cheeks were flushed.

‘It’s OK,’ Silas whispered as she switched the kettle on and rummaged in a drawer. ‘She’s not mad with you, just with that stupid woman.’

Andrea made us tea and handed the biscuits round. There were chocolate digestives. She smiled as I took one. ‘If I was on a desert island,’ she said, ‘and could take only one kind of biscuit, I’d take chocolate digestives.’

I frowned and grabbed the writing pad. They’d melt.

Andrea laughed. ‘You are far too sharp not to speak, Rafi, and too funny.’

Nice try, Andrea, but that wasn’t how I saw it.

‘So that was a very negative memory associated with not speaking,’ she said as I munched my way through biscuit number two. ‘Can you think of any more positives to balance that out?’

To be honest, right at that point my view on co-operation changed. I might have felt like shutting down at the start of the session, but now I genuinely did want to think of some positives because that memory was just so depressing.

Make more friends.

Because, you know, perhaps I could. If I was a braver, speaking person, I could talk to Rachel. She was Silas’s friend, but I liked her and she was interesting. I would like to be able to tell her that.

In another world, on another planet, I might talk again. In this one, right now, I couldn’t really see it happening.

‘You seem to have lost some confidence since last time we met,’ Andrea said, proffering the biscuits again. ‘That’s a shame because you need to stay focused if we’re going to do this and that means you need to keep believing you can. Because you can, you know. There’s no physical reason for not speaking so that means it is possible, no matter how hard it may seem to you at the moment.’

She sat back in the chair and looked at me. Her face was calm, but Silas’s was a mass of frustration.

‘I thought she really wanted to do it this time,’ he said.

&nb

sp; I do . . . don’t . . . do . . . Oh, how can I want to when I don’t even know how it feels to talk any more?

‘I think she does or she wouldn’t be sitting here now,’ Andrea replied. ‘But it’s been a long time and there are some very big barriers to overcome first. Rome wasn’t built in a day and Rafi won’t be cured in one either! You have to be patient.’

He gave her a rueful smile. ‘I guess.’

‘You often see a backward slide before an improvement.’ She was talking to me as well as him. ‘It’s as if, when the sufferer begins to see there’s a real possibility of the mutism being over, when that starts to become tangible, they panic and retreat. But it’s a very important part of the process. It may look like moving backwards, but in fact it’s a giant step forward. Now, Rafi, I want you to take another step. I want you to think of one thing associated with you becoming mute that I don’t know about, and maybe even Silas doesn’t. And I want you to tell us. Can you try, please?’

One very obvious thing occurred to me. The thing I’d lied about last time. I was ashamed that first time, ashamed of what it would reveal about my family.

But something else had happened as Silas dragged up that prep school memory. At the time I was horrified about my mother going into the school to complain. I’d heard her shout so often. What if she did that in the school? I’d die. Better not to make a fuss. I stood in the hall as she was leaving me with Kerensa so she could go and raise hell with the Head – her description not mine. I stared and stared at her with tears falling down my face, willing her to understand, but she didn’t even look at me. It had to be her way of course. I hated her for doing that.

Now, looking back years later, I saw something different in that memory. I saw her anger at her child being hurt, and I saw her going all out to protect me.

A lump formed in my throat.

I’d never seen it that way before.

She was outside somewhere now, sitting in her car, waiting for us.

The lump in my throat pressed more painfully and my eyes stung with some unshed tears. Maybe a tiny bit of her did care about me.

I took hold of the pen again. It might be important to tell this. It might help me get better.

I didn’t tell the truth last time I was here. It wasn’t Carys I stopped talking to first. It was Mum. But she didn’t notice.

Andrea read what I’d written with her usual careful therapist’s give-nothing-away face, but Silas winced.

‘Why did you say it was Carys?’

She was the first one to realise. I did stop talking to her eventually, but Carys realised it before Mum did.

Could anyone blame me for thinking Mum didn’t care after that?

But she was here now. And she was waiting for me. Had I got it wrong back then? What if she cared more than I’d thought?

To love is so startling it leaves little time for anything else.

(Emily Dickinson)

CHAPTER 30

A new coffee shop had opened on the high street and Josie and I went to try it out on Friday after school. It wasn’t one of the big chains but a rip-off looky-like. But the coffee was just as good, and the cookies. Plus it was right on our doorstep and not much was. It got our seal of approval all right.

Josie was telling me about a fantastic plan she’d come up with for us for the weekend. We were going to the zoo tomorrow. I had never been to the zoo before, not even on a school trip. This was another thing I loved about Josie. Out of nowhere, she would come up with something exciting to do.

‘Always try to do something awesome at least once a month, that’s my motto!’ she said, as I grinned and waved my hands about in a general effort to show my appreciation of her efforts. ‘Life is too short to waste.’

I guess many people didn’t know the truth of that as well as she did.

Rachel, Toby and the group from sixth form came in. Rachel and the girls waved at us while they queued.

‘Your brother not with them?’ Josie asked.

That was odd. He’d told me he had something on with his friends after school. I shrugged.

Once they’d got their orders, they came over to sit at the table next to us.

‘Any good?’ Clare asked Josie, gesturing at her coffee mug.

‘Actually, yeah, very,’ Josie said. ‘We’re impressed.’

‘What’ve you done with Silas?’ Toby asked. ‘I thought he was hanging out with you guys tonight.’

I shook my head and pointed at them. They looked puzzled.

‘She thought he was with you,’ Josie explained.

‘No,’ Rachel said. ‘He hasn’t been out with us for a while. We pretty much only see him in school these days.’

Josie frowned, remembering as I was all the times Silas said he was with them . . . or rather, he hadn’t exactly said that, but he must have known that was what we thought.

So where was he?

‘Hmm,’ Rachel said, with a conspiratorial glance at Clare. ‘I think someone is seeing someone, don’t you?’

Toby glowered and sank down in his chair. Clare laughed. ‘I think so too.’

‘Aww, it’s nice,’ Rachel said. ‘I like her. She’ll be good for him, not like all those “yes, Silas, no, Silas” types he usually ends up with.’

Clare rolled her eyes. ‘He always ends up with them because they engineer it. I don’t think he’s ever actually asked one of them out properly on a date.’

So they all thought he was probably out with Lara. But why was he keeping it so quiet? Toby’s sullen face might be a clue to that.

‘Do you think he was with her that night he texted you to say he wasn’t coming home?’ Josie asked when we were on our way back to her place.

That stopped me in my tracks. Perhaps he had been. But if he was so into her, why hadn’t he told me? He’d always talked to me about things like that before.

I felt jealousy bite with jagged teeth.

The news was on when we got to Josie’s house and her dad was watching it while he was getting ready to go out to work, hastily eating a bowl of stir-fry at the kitchen counter.

‘Police from across the Home Counties have been drafted in to support the Metropolitan Police in managing tomorrow’s protest in the capital,’ the news reporter announced. ‘The anticipated protests by various groups about the level of profits made by the global multinationals have been causing concern. While many of the groups involved have made it clear they expect the protests to be peaceful, a significant minority are said to be preparing for the kind of disturbances London saw in the student riots. Angry at what they say is the exploitation of people in developing countries at the expense of the fat-cat West, their leaders have been using social media sites to whip up support for vandalism and occupation of premises tomorrow. London braces itself for disruption, and the police brace themselves for a difficult day.’

‘Are you involved in that?’ Josie asked.

‘Yeah, I’ve been pulled in. We all have.’ Her dad shook his head at the TV and carried on speed-eating his dinner.

‘I was going to ask him for a lift to the zoo,’ Josie whispered glumly. ‘Do you think your mum will drop us off and pick us up?’

I almost laughed. Of course she wouldn’t.

‘You could try,’ Josie said pleadingly.

I nodded. If she wanted me to do that, I’d better go home and ask now in case Mum was going out.

I was in luck. Mum was eating her dinner too. I scribbled a note: Josie’s dad was going to drop us off at the zoo tomorrow, but now he has to work. Could you take us and then pick us up please?

She stopped eating and looked at me. I felt her judge me again – why can you not ask me this with your voice? I always felt her judgement when she looked at me, always had done and I guess I always would.

‘Yes,’ she said, and my head almost fell off in shock. ‘What time do you want to go?’

CHAPTER 31

Dear Dad,

It’s been the longest day and I can’t tell y

ou all of it now, but I’ll tell you some of it while it’s still fresh in my mind.

I was scared Lara was going to be distant with me after our date, as it didn’t end at all according to plan. But she hasn’t. We’ve been hanging out together more, mostly in the library or the new coffee shop in town. Just half an hour here and there when she has time. But on our own more, like she’s happy to be alone with me now without Rachel and Toby and all the others around. I told her I wanted to see more of her and was that OK, and she said yes, but she was busy. She was a bit cagey about telling me why, but eventually I got it out of her. She’s been doing some campaigning for those people who ran the meeting she took me to, ActionX. Said they were doing some good work at the moment and she wanted to give some support. Then she told me about a march in London and asked me if I wanted to come with her.

I felt like it was a test. Obviously, Dad, you know I had to pass it. And when she told me what it was about, well, they’ve got a point. Someone should be stopping this stuff from going on.

She met me at the train station. She had this little smile when she saw me, this little smile that totally slayed me. My heart leaped so high I wondered how it could still be in my chest. It was . . . trusting of me in a way I’d never seen from her before. With it, and with every move, every word, more and more, she reels me in and I don’t care how fast I’m caught.

‘Hey,’ she said. ‘So are you still up for this?’

‘Completely.’

‘You know it could get heavy?’

‘I know.’

She grinned. The platform announcer called the train. ‘Let’s do this then,’ she said.

There was evidence of what was coming even at the station when we got off the train in London. I could see it in a grimness around the eyes and the mouths of some of the people making their way down to the Embankment where the march was scheduled to start. Professional protesters, all looking like the ActionX people, a sameness to how they dressed and, yes, a sameness to their expressions on a day like this. I glanced at Lara – I could see it in her face too, that strange elation and a sort of deadliness.

Louder Than Words

Louder Than Words