- Home

- Laura Jarratt

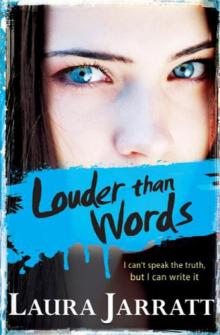

Louder Than Words Page 2

Louder Than Words Read online

Page 2

‘That was so weird,’ he said, once we were out of hearing. ‘Toby tells us about this girl and then . . .’ He looked down at me. ‘I feel so sorry for her. She’s in bits.’

And that’s my brother again. He doesn’t care if he’s supposed to feel sorry for her, whether that’s a ‘boy’ thing to do. He just does, so that’s it. All the same I glared at him for that trick of inviting her round.

‘Don’t look at me like that. I hope she does come round to see you. From what Toby said nobody in her school is speaking to her any more, especially the other girls. You know how mean girls can be about things like that and she looks like she could use a friend.’

He didn’t add that I could too.

Back at home, my mother was nowhere in sight and there was a note on the fridge. ‘Back at seven. Make food. Seeing a gallery about a sculpture.’

Silas sighed and opened the fridge. ‘What do you fancy for dinner? I could do pasta and meatballs. Needs to be something quick – I’ve got an essay to write for tomorrow.’

That was fine with me so he whipped up some food while I sat at the dining table and got my homework out of my bag. It was typical of Mum to disappear off to London without telling us this morning. She was quite capable of simply forgetting to communicate things like that.

Silas threw a quick bowl of salad together as well as the pasta and sat down with me to eat while he read through the text he had to write the essay on. He had a frown crease between his eyes so I left him to get on with it and flicked through a magazine while I ate. The food tasted good – he wasn’t a bad cook when it came to simple stuff. Much better than me anyway. And better than Mum.

Sitting round this table, that was my first real memory of my family. I must have been about three because Silas looks around six in my mind. We were all sitting down for Sunday lunch. The others were still at home then: my oldest sister Carys, who played the flute so well that she’d be off to a specialist music academy soon and then on to a glittering international career as a soloist; Gideon, who inherited Mum’s artistic talent and had already had his first exhibition, aged twelve; Kerensa, who did her maths A level before she was ten; and Silas, who was flicking peas at me when Mum wasn’t looking.

Silas at six was beautiful. So much so that people stopped Mum in the street to tell her. He had dark hair that waved a little, but was cropped short enough so that no one mistook him for a girl, eyes the blue of the Mediterranean Sea when it’s painted by the light of a summer sky – a colour I would kill to have – with curling black eyelashes so long they looked as if they’d rest on his cheeks when he was asleep. I don’t of course remember these details from when I was three. I’ve seen the photos and at seventeen he’s sickeningly unchanged. I do look a little like him, people say, but what they mean is, if he’s a painting, I look like a practice version that’s had water spilled on it and is left washed out and smudged.

But I didn’t know any of this in the memory. What I knew then was that Silas had just hit me in the face with a pea and it was funny. About two seconds later, when Mum noticed the gravy stain on my clean T-shirt, she found it less funny and exploded into one of her legendary rants. The family stopped eating and winced, and Silas burst into tears.

I didn’t like the shouting and the big, fat, salty drops rolling down my brother’s cheeks so I started to cry too. Dad stormed from the table, shouting, ‘Is there never any peace in this wretched house?’ and another Ramsey family lunch was ruined.

Mum didn’t have any more babies after me because not long after that Sunday lunch, Dad left us. He ran away with an ordinary woman who didn’t stress about gravy stains on a child’s T-shirt and he didn’t see us any more. Silas told me he’d wanted to, but Mum wouldn’t let him so that was that. Dad didn’t fight for us, but then Mum says he never fought for anything except to get away from her.

I wonder if I’d have become mute if he’d still been around. Probably. I don’t think him abandoning us had too much to do with it. Except he was more ordinary than the rest, like me, so maybe it would have been easier for me if he’d stayed – that would have made two of us the boring ones among the exceptional Ramseys.

CHAPTER 2

It could all have ended there, with a girl we met on the street, crying because of a stupid Facebook prank, and I suppose it would have done if Josie hadn’t come round to our house. But Silas had invited her and that set in motion the whole chain of events leading to now.

She didn’t come over that evening or the next day or even the one after that. But on Saturday morning the bell on our front gates rang shortly after breakfast and Mum answered.

‘Hello?’

‘Hi, um, this is Josie. I live down the street. I’ve come to see Rafi.’

There was a stunned pause. My mother raised an eyebrow at the intercom receiver in her hand and then she buzzed Josie in. She turned to find me standing in the kitchen doorway. ‘Apparently it’s for you.’

I nodded, faking nonchalance. Suddenly I was a whirl of nerves inside. Josie had come to see me, but how would I communicate with her? This was why I didn’t have friends. Without Silas as my interpreter, how could I make myself heard? Nobody but Silas understood me.

‘Well, this should be interesting,’ my mother remarked tartly as she sat down at the kitchen table and began flipping through the culture supplement in the newspaper.

I could feel my hands begin to tremble and my throat tightened.

‘You should let her in,’ my mother added and I heard the exasperation in her voice.

Of course I should. Josie must be at the door by now and wondering whether to ring the bell there too. How stupid of me. I hurried to the front door and wrenched it open just as Josie’s hand hovered over the brass bell button.

‘Ah, hi!’ she said, and to my surprise she looked as nervous as I felt. ‘Hope you don’t mind me coming over. I wasn’t sure if you really meant it when you invited me, but then I thought if you did it would be so rude if I didn’t after you guys were nice to me when I was upset and –’ She paused to gulp in a breath. ‘I should shut up. I talk too much.’

And me not enough, I thought. I smiled uselessly and shook my head to say I didn’t think so. She looked confused for a moment and then I think she figured out what that meant because she nodded and said, ‘That’s kind of you, but I know I do really. Sometimes I should just, you know, stop babbling on.’

I stood aside and beckoned her in. There wasn’t a day that went by when my lack of words didn’t make me feel stupid at some time or other, but I rarely felt the loss as acutely as I did at this precise moment. And my throat felt more closed than ever.

‘Thanks.’ She looked around our hall with interest. ‘Wow, I’ve never seen so many paintings.’

Like every room in the house, the walls were lined with pictures. None of them were my mother’s – she wasn’t that vain – but all of them were chosen by her. Some were free, from artist friends, others she’d bought over the years and several were Gideon’s. Probably even Gideon’s finger paintings when he was two were special. Unlike other mothers, she’d never put any of her other children’s attempts up – Silas’s and my portraits of cats and houses and Christmas trees had never defaced the kitchen cupboards. Gideon’s efforts had earned their place through merit alone.

‘Our mother’s an artist.’

We turned round to see a sleep-ruffled Silas coming down the stairs wearing a pair of boxers and, thankfully, a T-shirt. On Saturdays, my brother didn’t rise from his pit until the sun was well up in the sky, usually because he was messing around online most of Friday night, doing some geeky computer stuff with his geeky internet friends. For that was Silas’s special thing: he wasn’t an artist or a musician or a maths boffin; he did things with computers. What exactly he did was beyond my understanding, but whatever it was I knew he was good at it from the reverential way his friends spoke to him about that kind of thing.

Josie looked flustered. ‘Oh, right.’

; ‘Want coffee or juice or something?’

Of course. That’s what normal people did – offered their guests a drink. Doh! I sucked in a breath and tried to work out how to operate in some kind of normal girl mode. I could give up and just leave it all to Silas or let Josie go away and not have the stress of working out how I was going to communicate with her. But here she was, standing in my hall, and I had this crazy feeling that I was this close, this close, to making a connection. It was terrifying, but at the same time so exciting I thought I might burst.

I jerked my head at her, smiling again, and my face was starting to freeze up from the effort of grinning to replace the useless words that never escaped my throat. I walked through to the kitchen and she followed me, with Silas trailing behind, rubbing sleep from his eyes. I wondered what she thought of my brother in that state. I noticed she avoided looking at him directly, seeming to find her feet more interesting.

My mother gave her a polite but distant nod as she folded up the newspaper. I thought for a moment I detected a flash of curiosity from her, but then she got up to leave. ‘I must get on. I need to get those three pieces finished for the Bartlett commission.’ She drifted out of the room in a suitably ‘arty’ fashion. Josie looked impressed, if a little intimidated. Silas and I rolled our eyes at each other. It was less impressive when you lived with it.

‘Exit stage left,’ muttered Silas and flicked the kettle on.

He was about to ask Josie what she wanted to drink, but that was wrong. She was my guest and I should be doing it. I yanked the fridge door open and held up the juice carton, and simultaneously pointed to the coffee jar on the worktop.

‘Oh, juice would be great, thanks.’

I beamed. It felt as if the grin exploded across my face. Such a stupid little thing that would seem to anyone else, but to me at that moment it was a breakthrough of the highest order. I had done it. Normal communication established. Me! I connected!

I was so happy that I almost forgot to pour the juice for her, but then I pulled myself together. It was a good job she couldn’t see how thrilled I was or she’d think I was a complete loser.

Why did her opinion matter to me? I didn’t know her at all, only met her once and then very briefly. Was it a premonition of friendship or just that a chance seemed – incredibly – to be presenting itself and I so badly didn’t want to blow it? I don’t think I ever worked out the answer. But it didn’t matter: what was to be would be.

I set her juice down on the table and got myself a glass too, as Silas mooched around making coffee and toast and tactfully ignoring us. I could have hugged him for that.

‘So I figured I should come and say thank you for . . . oh, that you stopped to see if I was OK the other day, that you cared,’ Josie said, sipping juice. ‘I mean, most people wouldn’t. Even my so-called friends don’t. They all think it’s one great big joke. Easy for them when it’s not them on the receiving end!’

I pulled a puzzled face, which was a bit duplicitous of me, but what was I supposed to do – let her know I knew what she was talking about and the gossip was all over my school too?

‘Oh yeah, sorry, this won’t make any sense to you.’ She sighed heavily. ‘I don’t really want to explain because it hurts to even talk about it, but . . .’ She took a deep breath. ‘Well, we can’t be friends if I’m pretending about why I was upset that day, can we?’

I shook my head, dazed. So she really did want to be friends. It wasn’t some silly daydream I was having. She honestly, truly wanted to be friends with me.

Nobody had ever wanted to be friends with me before.

Unless she had other motives.

I looked up at Silas leaning against the kitchen counter and munching toast with peanut butter. Maybe it was Silas that Josie really wanted to be around. Was I just a convenient way to get closer to him?

I frowned. Hmm, maybe my nasty, suspicious mind was just that – nasty and suspicious. But why would a Year 11 girl – who was pretty and, according to Toby, had been popular before her ex trashed her reputation – want to be friends with me?

Josie looked at me with a puzzled expression so I tried to wipe the frown away.

It worked. As my frown disappeared, so did her puzzlement and she took a deep breath in. ‘Look, I don’t normally talk like this to complete strangers I meet in the street, but I think gut reactions are really important and, this is going to sound mental, but I had a really strong one when I met you, like I just knew we’d be friends. Some kind of instant connection. Did you feel anything like that?’

Did I? Yes, perhaps that was what I was feeling, that unexpected sense of wanting to communicate with a girl I didn’t know, a feeling that had come out of nowhere and left me shaken at the strangeness. That kind of need was so foreign to me. Maybe this was how friendships started. I suppose Josie would know that better than me. I nodded slowly.

Josie beamed. She had one of those transformational smiles that turned her into someone you wanted so much to be with. ‘Oh good!’

She glanced at Silas, who had picked up our mother’s newspaper and was sitting on a stool at the furthest end of the long kitchen counter studiously ignoring us. I wasn’t fooled. He ‘wasn’t listening’ with exactly the same face I used when I ‘wasn’t listening’ to his friends. But Josie fell for it.

‘I don’t normally cry in the street,’ she said. ‘I said I’d had a really bad day. Well, it was beyond bad. It’s been like the most completely sucky week of my whole life.’ She paused and added, ‘You’re a really good listener, do you know that? I mean, you don’t nod all the time and obviously you don’t answer, but it’s in your eyes that you’re listening. And there’s something else there too . . . that you won’t judge.’ She shook her head slightly as if she’d surprised even herself with that insight and then she went on. ‘Even my friends were horrible about what happened. They won’t even speak to me now and . . . oh, this will be making no sense at all. I’ll have to start at the beginning, but tell me if I’m boring you and I’ll stop, OK?’

Yes, that was OK, but I couldn’t see myself getting bored. I wanted to know her side of it; after all, Toby’s wasn’t likely to be totally accurate.

‘Have you ever been in love? Dumb question I guess because you probably haven’t yet, but I could be wrong. No? You will be one day. I thought I was. It’s the strangest feeling. It’s like it takes over your whole life. Like you’re not even yourself any more. Like you’re whoever the person you love wants you to be even if that’s not who you know you are deep down. You change.’ She checked my face. ‘You look doubtful. Maybe you’re right. Maybe you don’t really change and you just pretend. No? Or do you think that’s not really love at all. Yeah, you could be right about that too. I’m not sure either. Like I said, I thought I was in love. Now I’m not so sure I ever was. All I know is I hate him now.’

That wasn’t unexpected. If someone had betrayed me like that, I’d hate him too.

‘His name’s Lloyd and he’s in the year above me, but he’s not at my school. He goes to college to do engineering. My dad didn’t know I was going out with him or he’d have grounded me for life. Dad’s in the police and Lloyd got in some trouble last year for under-age driving. That’s how I met him – he was driving around the leisure centre car park in his cousin’s car one night after I came out from my swim club meet, but this was after he’d got in trouble the first time. So he was doing it again. I know, I know what you’re thinking, and yes, obviously he is completely stupid, but so must I be too because all I could think when I met him was how cute he was. I didn’t find out about the trouble with the police until later and by then I was so into him that I told myself it didn’t matter. I made so many excuses for him.’

At least she could see that now. That was something.

She got her phone out and showed me a picture. ‘That’s him.’ And yes, it was clear what she’d seen in him. He looked as dodgy as anything and I would have run a mile from a boy like him, but he had that b

ad-boy grin that some girls find irresistible, and he was easy on the eye, I had to admit.

‘So I was crazy about him; you have to understand that part or none of this makes any sense and you’ll think I’m just some slut who –’

I thought she was going to cry for a moment, but she took a few breaths and managed not to.

‘Sorry. We’d been seeing each other a few months when he invited me to his cousin’s party. Everyone there was wasted and I know I drank too much too, but I wasn’t completely out of it – I can’t use that as an excuse. I did know what I was doing, but . . . I trusted him. That’s how stupid I am. I trusted that pig and . . .’ Her eyes started filling up with tears.

I got up hurriedly and tore off some kitchen roll for her. Silas sat rooted to his stool like a tree, and stared at the paper like he was deaf and invisible. I wondered whether Josie felt more uncomfortable saying this in front of him. Or did she want him to know the truth? If she was interested in him . . .

‘Thanks. I didn’t mean to cry again. It’s so silly. I’m not crying over him. I am so totally over him I can’t understand why I ever liked him now. It’s because I feel such an idiot. Everyone’s laughing at me and the more they do, the worse it gets because it encourages him. I begged him to stop, though I hated myself for doing it because I bet it gives him a buzz to make me beg, but he won’t. Just keeps putting worse and worse stuff online about me.’

OK, so I knew he’d posted some pictures, but it was still going on? I shook my head at her to show I didn’t understand.

‘Yeah, I know. I’m being rubbish at explaining.’ She wiped her face with the paper towel. ‘Basically, after that party I went back to his to get changed before going home. My dad’s really strict and I didn’t want him smelling smoke and alcohol on me. While I was getting changed, Lloyd sneaked into the bedroom and took some photos of me. I didn’t have my bra on in some of them. I sort of yelled at him when I realised he was there, bu t he made out like it was a big joke and we’d both had too much to drink so, yes, I was dumb and I started laughing too. Then he talked me into posing for a couple of photos. Just messing around, he said, but he kept kissing me and telling me I was beautiful, and he just wanted something to remind him just how beautiful when I wasn’t there.’

Louder Than Words

Louder Than Words